Lowering the nuclear threshold and other follies of the new Nuclear Posture Review

Article de « War is boring » du 1er mars

If you’re having trouble sleeping thanks to, well, you know who … you’re not alone. But don’t despair. A breakthrough remedy has just gone on the market. It has no chemically induced side effects and, best of all, will cost you nothing, thanks to the Department of Defense.

It’s the new Nuclear Posture Review, or NPR, among the most soporific documents of our era. Just keeping track of the number of times the phrase “flexible and tailored response” appears in the 75-page document is the equivalent of counting incinerated sheep.

Be warned, however, that if you really start paying attention to its actual subject matter, rising anxiety will block your journey to the slumber sphere.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that the United States devoted $611 billion to its military machine in 2016. That was more than the defense expenditures of the next nine countries combined, almost three times what runner-up China put out, and 36 percent of total global military spending.

Yet reading the NPR you would think the United States is the most vulnerable country on Earth. Threats lurk everywhere and, worse yet, they’re multiplying, morphing, becoming ever more ominous. The more Washington spends on glitzy weaponry, the less secure it turns out to be, which, for any organization other than the Pentagon, would be considered a terrible return on investment.

The Nuclear Posture Review unwittingly paints Russia, which has an annual military budget of $69.2 billion — $10 billion less than what Congress just added to the already staggering 2018 Pentagon budget in a deal to keep the government open — as the epitome of efficient investment, so numerous, varied, and effective are the “capabilities” it has acquired in the 17 years since Vladimir Putin took the helm.

Though similar claims are made about China and North Korea, Putin’s Russia comes across in the NPR as the threat of the century, a country racing ahead of the U.S. in the development of nuclear weaponry. As The Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler has shown, however, that document only gets away with such a claim by making 2010 the baseline year for its conclusions.

That couldn’t be more chronologically convenient because the United States had, by then, completed its latest wave of nuclear modernization. By contrast, during the decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia’s economy contracted by more than 50 percent, so it couldn’t afford large investments in much of anything back then. Only when oil prices began to skyrocket in this century could it begin to modernize its own nuclear forces.

The Nuclear Posture Review also focuses on Russia’s supposed willingness to launch “limited” nuclear strikes to win conventional wars, which, of course, makes the Russians seem particularly insidious. But consider what the latest iteration of Russia’s military doctrine actually says about when Moscow might contemplate such a step. “The Russian Federation reserves the right to use nuclear weapons in response to the use of nuclear and other types of weapons of mass destruction against it and/or its allies, and also in the case of aggression against the Russian Federation with the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy.”

Reduced to its bare bones this means that countries that fire weapons of mass destruction at Russia or its allies or threaten the existence of the Russian state itself in a conventional war could face nuclear retaliation. Of course, the United States has no reason to fear a massive defeat in a conventional war — and which country would attack the American homeland with nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons and not expect massive nuclear retaliation?

Naturally, the Nuclear Posture Review also says nothing about the anxieties that the steady eastward advance of NATO — that ultimate symbol of the Cold War — in the post-Soviet years sparked in Russia or how that shaped its military thinking. That process began in the 1990s, when Russian power was in free fall. Eventually, the alliance would reach Russia’s border. The NPR also gives no thought to how Russian nuclear policy might reflect that country’s abiding sense of military inferiority in relation to the United States.

Even to raise such a possibility would, of course, diminish the Russian threat at a time when inflating it has become de rigueur for liberals as well as conservatives and certainly for much of the media.

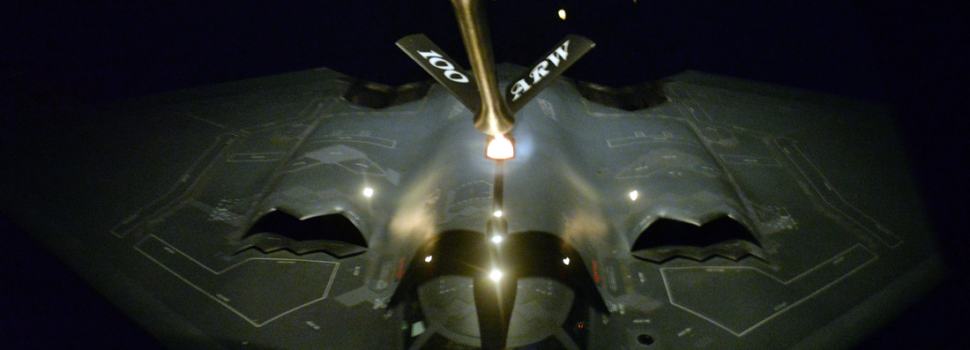

At top — a U.S. Air Force B-2 bomber. Air Force photo. Above — an Ohio-class submarine. U.S. Navy photo

Strangelove logic

Russian nuclear weapons are not, however, the Nuclear Posture Review’s main focus. Instead, it makes an elaborate case for a massive expansion and “modernization” of what’s already the world’s second largest nuclear arsenal — 6,800 warheads versus 7,000 for Russia — so that an American commander-in-chief has a “diverse set of nuclear capabilities that provide … flexibility to tailor the approach to deterring one or more potential adversaries in different circumstances.”

The NPR insists that future presidents must have advanced “low-yield” or “useable” nuclear weapons to wield for limited, selective strikes. The stated goal — to convince adversaries of the foolishness of threatening or, for that matter, launching their own limited strikes against the American nuclear arsenal in hopes of extracting “concessions” from us.

This is where Strangelovian logic and nuclear absurdity take over. What state in its right mind would launch such an attack, leaving the bulk of the U.S. strategic nuclear force, some 1,550 deployed warheads, intact? On that, the NPR offers no enlightenment.

You don’t have to be an acolyte of the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz or have heard about his concept of “friction” to know that even the best-laid plans in wartime are regularly shredded. Concepts like limited nuclear war and nuclear blackmail may be fun to kick around in war-college seminars.

Trying them out in the real world, though, could produce disaster. This ought to be self-evident, but to the authors of the NPR it’s not. They portray Russia and China as wild-eyed gamblers with an unbounded affinity for risk-taking.

The document gets even loopier. It seeks to provide the commander-in-chief with nuclear options for repelling non-nuclear attacks against the United States, or even its allies. Presidents, insists the document, require “a range of flexible nuclear capabilities,” so that adversaries will never doubt that “we will defeat non-nuclear attacks.”

Here’s the problem, though. Were Washington to cross that nuclear Rubicon and launch a “limited” strike during a conventional war, it would enter a true terra incognita. The United States did, of course, drop two nuclear bombs on Japanese cities in August 1945, but that country lacked the means to respond in kind.

However, Russia and China, the principal adversaries the NPR has in mind — though North Korea gets mentioned as well — do have just those means at hand to strike back. So when it comes to using nuclear weapons selectively, its authors quickly find themselves splashing about in a sea of bizarre speculation. They blithely assume that other countries will behave precisely as American military strategists or an American president might ideally expect them to and so will interpret the nuclear “message” of a limited strike and its thousands of casualties, exactly as intended.

Even with the aid of game theory, war games, and scenario building — tools beloved by war planners — there’s no way to know where the road marked “nuclear flexibility” actually leads. We’ve never been on it before. There isn’t a map. All that exists are untested assumptions that already look shaky.

A Minuteman III missile. U.S. Air Force photo

Yet more nuclear options

These aren’t the only dangerous ideas that lie beneath the NPR’s flexibility trope. Presidents must also, it turns out, have the leeway to reach into the nuclear arsenal if terrorists detonate a nuclear device on American soil or if conclusive proof exists that another state provided such weaponry or materials to the perpetrator or even “enabled” such a group to “obtain nuclear devices.”

The NPR also envisions the use of selective nuclear strikes to punish massive cyberattacks on the United States or its allies. To maximize the flexibility needed for initiating selective nuclear salvos in such circumstances, the document recommends that the United States “maintain a portion of its nuclear forces alert day-to-day, and retain the option of launching those forces promptly.”

Put all this together and you’re looking at a future in which nuclear weapons could be used in stress-induced haste and based on erroneous intelligence and misperception.

So while the NPR’s prose may be sleep inducing, you’re unlikely to nod off once you realize that the Trump-era Pentagon — no matter the NPR’s protests to the contrary — seeks to lower the nuclear threshold. “Selective,” “limited,” “low yield.” These phrases may sound reassuring, but no one should be misled by the antiseptic terminology and soothing caveats.

Even “tactical” nuclear weapons are anything but tactical in any normal sense. The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki might, in terms of explosive power, qualify as “tactical” by today’s standards, but would be similarly devastating if used in an urban area. We cannot know just how horrific the results would be, but the online tool NUKEMAP calculates that if a 20-kiloton nuclear bomb, comparable to Fat Man, the code name for the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, were used on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where I live, more than 80,000 people would be killed in short order.

Not to worry, the NPR’s authors say, their proposals are not meant to encourage “nuclear war fighting” and won’t have that effect. On the contrary, increasing presidents’ options for using nuclear weapons will only preserve peace.

The Obama-era predecessor to Trump’s Nuclear Posture Review contained an entire section entitled “Reducing the Role of U.S. Nuclear Weapons.” It outlined “a narrow set of contingencies in which such weaponry might still play a role in deterring a conventional or CBW [chemical or biological weapons] attack against the United States or its allies and partners.” So long to that.

U.S. Air Force F-15Es. Air Force photo

The tab

Behind the new policies to make nuclear weapons more “useable” lurks a familiar urge to spend taxpayer dollars profligately. The Nuclear Posture Review’s version of a spending spree, meant to cover the next three decades and expected, in the end, to cost close to two trillion dollars, covers the works. The full nuclear “triad” — land-based ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ones, and nuclear-armed strategic bombers. Also included are the nuclear command, control and communication network — NC3 — and the plutonium, uranium and tritium production facilities overseen by the National Nuclear Security Administration.

The upgrade will run the gamut. The 14 Ohio-class nuclear submarines, the sea-based segment of the triad, are to be replaced by a minimum of 12 advanced Columbia-class boats. The 400 Minuteman III single-warhead, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, will be retired in favor of the “next-generation” Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, which, its champions insist, will provide improved propulsion and accuracy — and, needless to say, more “flexibility” and “options.”

The current fleet of strategic nuclear bombers, including the workhorse B-52H and the newer B-2A, will be joined and eventually succeeded by the “next-generation” B-21, a long-range stealth bomber. The B-52’s air-launched cruise missile will be replaced with a new Long Range Stand-Off version of the same. A new B61-12 gravity bomb will take the place of current models by 2020. Nuclear-capable F-35 stealth fighter-bombers will be “forward deployed,” supplanting the F-15E. Two new “low-yield” nuclear weapons, a submarine-launched ballistic missile and a sea-launched cruise missile will also be added to the arsenal.

Think of it, in baseball terms, as an attempted grand slam.

The NPR’s case for three decades of such expenditures rests on the claim that the “flexible and tailored” choices it deems non-negotiable don’t presently exist, though the document itself concedes that they do. I’ll let its authors speak for themselves. “The triad and non-strategic forces, with supporting NC3, provide diversity and flexibility as needed to tailor U.S. strategies for deterrence, assurance, achieving objectives should deterrence fail, and hedging.”

For good measure, the NPR then touts the lethality, range and invulnerability of the existing stock of missiles and bombers. Buried in the review, then, appears to be an admission that the colossally expensive nuclear modernization program it deems so urgent isn’t necessary.

The NPR takes great pains to demonstrate that all of the proposed new weaponry, referred to as “the replacement program to rebuild the triad,” will cost relatively little. Let’s consider this claim in wider perspective.

To obtain Senate ratification of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty he signed with Russia in 2010, the Nobel Prize-winning antinuclear advocate Barack Obama agreed to pour $1 trillion over three decades into the “modernization” of the nuclear triad, and that pledge shaped his 2017 defense budget request.

In other words, Obama left Trump a costly nuclear legacy, which the latest Nuclear Posture Review fleshes out and expands. There’s no indication that the slightest energy went into figuring out ways to economize on it. A November 2017 Congressional Budget Office report projects that Trump’s nuclear modernization plan will cost $1.2 trillion over three decades, while other estimates put the full price at $1.7 trillion.

As the government’s annual budget deficit increases — most forecasts expect it to top $1 trillion next year, thanks in part to the Trump tax reform bill and Congress’s gift to the Pentagon budget that, over the next two years, is likely to total $1.4 trillion — key domestic programs will take big hits in the name of belt-tightening. Military spending, of course, will only continue to grow. If you want to get a sense of where we’re heading, just take a look at Trump’s 2019 budget proposal, which projects a cumulative deficit of $7.1 trillion over the next decade.

It urges big cuts in areas ranging from Medicare and Medicaid to the Environmental Protection Agency and Amtrak. By contrast, it champions a Pentagon budget increase of $80 billion — 13.2 percent over 2017 — to $716 billion, with $24 billion allotted to upgrading the nuclear triad.

And keep in mind that military cost estimates are only likely to rise. There is a persistent pattern of massive cost overruns for weapons systems ordered through the government’s Major Defense Acquisition Program. These ballooned from $295 billion in 2008 to $468 billion in 2015. Consider just two recent examples. The first of the new Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carriers, delivered in May 2017 after long delays, came in at $13 billion, an overrun of $2.3 billion, while the program to produce the F-35 jet, already the most expensive weapons system of all time, could reach $406.5 billion, a seven percent overrun since the last estimate.

A U.S. Air Force F-16 with a B61 bomb. Air Force photo

Flexibility follies

If the Pentagon turns its Nuclear Posture Review into reality, the first president who will have some of those more “flexible” nuclear options at his command will be none other than Trump. We’re talking, of course, about the man who, in his debut speech to the United Nations last September, threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea and later, as the crisis on the Korean peninsula heated up, delighted in boasting on Twitter about the size of his “nuclear button.”

He has shown himself to be impulsive, ill informed, impervious to advice, certain about his instincts, and infatuated with demonstrating his toughness, as well as reportedly fascinated by nuclear weapons and keen to see the United States build more of them. Should a leader with such traits be given yet more nuclear “flexibility”? The answer is obvious enough, except evidently to the authors of the NPR, who are determined to provide him with more “options” and “flexibility.”

At least three more years of a Trump presidency are on the horizon. Of this we can be sure. Other international crises will erupt, and one of them could pit the United States not just against a nuclear-armed North Korea but also against China or Russia. Making it easier for Trump to use nuclear weapons isn’t, as the Nuclear Posture Review would have you believe, a savvy strategic innovation. It’s insanity.

Rajan Menon is the Anne and Bernard Spitzer Professor of International Relations at the Powell School, City College of New York, and Senior Research Fellow at Columbia University’s Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies. He is the author, most recently, of The Conceit of Humanitarian Intervention. This story originally appeared at TomDispatch.